Make the Price Work in Your Favour

We all believe that we compare prices rationally and objectively. The reality is far from it. The price is always relative and what we consider cheap or expensive can be influenced.

Behavioral economics and psychology professor Dan Ariely has demonstrated how we become irrational when dealing with money in a number of experiments. In one of his experiments, the subjects were given the choice of buying a Ferrero Rocher chocolate for 26 cents or a Hershey’s Kiss for 1 cent. 40% of the participants chose Ferrero and another 40% chose the Kiss.

When the prices were reduced by 1 cent, 90% of the people chose the Kiss, although the price difference between the two treats was still 25 cents. It’s just that the Hershey’s Kiss was free, and something being “free of charge” is a force to be reckoned with.

An equally powerful force is gaining something tangible. An experiment conducted by Minnesota University scientist Akshay Rao revealed that people bought 73% more hand cream when the package included a bonus cream tube compared to when the price was lowered by an equivalent amount.

People just didn’t understand that increasing the amount of the product by 50% is equal to reducing the price of the product by 33%. The blindness to numbers continued to prevail when people made purchase decisions that clearly did them a disservice, i.e. when the price was again lowered by 33% but the bonus tube no longer contained 50% more product but only 33% more. The majority still chose the bonus package and were satisfied with their decision.

People also believed that they benefitted more when a product was first discounted by 20% and then a further 25%, instead of a single equivalent 40% discount.

In Entrepreneur, Marketing professor, and strategy manager at Canadian agency Jelly Marketing, Darian Kovacs lists four methods that implement psychology to make people buy and walk away believing they’ve struck a great deal.

A decoy price allows you to confuse us. For example, if a small beer at a bar costs $4 and large costs $9, the customer will find it easy to decide in favor of the small beer. However, if you include a third price – small beer $4, medium beer $8 and large beer $9 – it’ll be easy to decide in favor of the large beer. The large is, after all, only a dollar more expensive than the medium. National Geographic Channel reached a similar conclusion in their experiment featuring popcorn packages. In psychology, this phenomenon that causes people to believe distorted and illogical information is called cognitive bias.

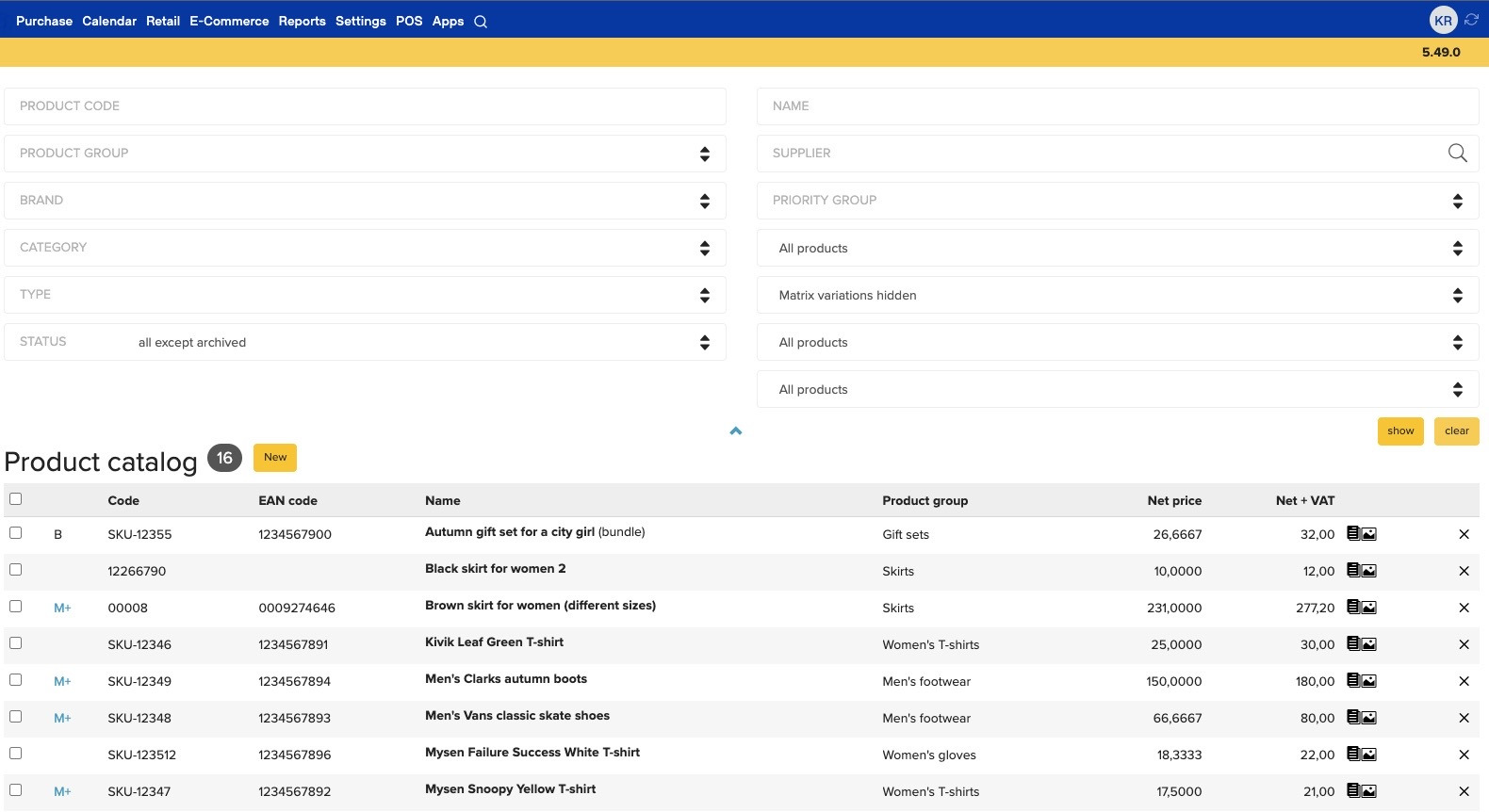

Another classic option is bundling. As neuromarketing consultant and author Roger Dooley explains in his book Brainfluence, seeing a steep price activates the part of the brain responsible for processing pain. Bundling is an easy way to ease that pain because it’s difficult to grasp the price of an individual item from a bundle.

This method is common among book and, increasingly frequently, car sellers. The latter no longer list all the extras (e.g. leather seats, a better audio system, etc.) individually in the price list but rather sell a combination as different package deals. Bundling is an age-old method that’s also ideal for popularising new products and much more. However, it isn’t the best idea to bundle a cheap and expensive item. Experiments have shown that the cheap item will deduct the value of the purchase for the buyer, making him/her unwilling to pay even the price of the more expensive product for the entire bundle.

The third method is anchoring and is based on how a person creates a reference price in their head every time they consider buying a product. This reference price will be used to determine whether your product’s price is acceptable or expensive. The beauty lies in the fact that the reference price can be manipulated. This phenomenon is called anchoring bias.

When a person has to make a (purchase) decision, their subconscious will begin seeking additional information. The first bit of information they encounter will be “anchored” in the mind and have a significant effect on the decision. The most common way of achieving this is a play on prices. The former higher price has been crossed out on the price tag but is clearly visible. The new price now seems significantly cheaper compared to if that were the only price on the tag.

Anchoring doesn’t only concern prices. For example, if you’re looking to buy a used car and someone strategically directs your attention to the mileage, your subconscious will become anchored to it and you may easily fail to take note of the service history, corrosion, the state of the wheel and breaks, etc.

The foot-in-the-door technique concentrates on getting a small “yes” from the customer to make getting the big “yes” that much easier. A classic study on this was organized in 1966 by behavioral scientists who asked a group of people to place a small sticker promoting safe driving on their car. The other group didn’t have to do anything. A couple of weeks later, all of the participants were asked to install a large poster on their lawn to promote safe driving. The people who had been given the sticker tended to agree to do so while the other group was not that fond of the idea. One of the more widespread foot-in-the-door methods is being able to download a free eBook in exchange for your email address. Only then will the offers for other products start popping up in your mailbox.

Two other pricing methods have stood the test of time. KPCB partner Bing Gordon hails “Rethink fairness!” and suggests hacking a $1,000 sum into pieces. Paying 84 euros in twelve installments doesn’t sound all that bad. The pain is gone! It doesn’t even matter that the customer actually ends up paying a little more than a thousand dollars over the twelve months.

And last but not least, deduct the even number by one cent! Not $10 but $9.99. The charm pricing method still works. Even though we all know we are being duped (the price is only one cent less than ten dollars), the brain likes to think it’s nine instead of ten.

Scientists Thomas and Morwitz from Cornell University have researched this method and point out that it doesn’t work always and in every context. Among else, it’s important that the number on the left also decreases. So 5.60 vs. 5.59 won’t work but 5.00 vs. 4.99 will.

However, some research indicates that when it comes to certain products, especially the more luxurious kind (e.g. champagne), a whole price might work best – so not 49.99 but a nice 50 even.

Literature is abundant with price tactics that are based on psychology. However, the tactics that work in a jewelry shop will most likely not work in a small grocery shop. But the fact that it’s so easy to affect people’s purchases with prices only means one thing – experiment!